Tell me about your current role at Yale University:

I’ve been at Yale eighteen years. I was at the library for 7 years, then the rest of the time at the med school. Currently I’m supervisor of traffic, receiving and stores, medical area and medical mail room.

Would you share some of your military experience and transition to the private sector:

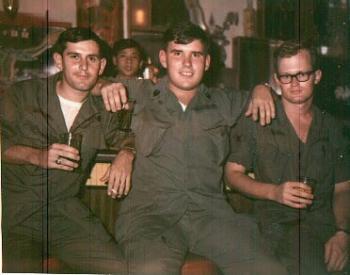

I went into the military in August ’67 because I was a total goof-off in high school. I had at best a C- average. My guidance counselor cried. She said “I think I can get you into some college somewhere.” And I thought, “The heck with that, I’m going to do better than that, I’m not going to pay for my own college, I’m going to join the army.” So I went in for four years, because at that time if you did two years they paid for two years of college. I did 20 months in Vietnam, and 11 months in Korea. And then I got out, and went to college on the GI Bill, and eventually ended up with my MBA in 1987, paid for by my company at that time.

What company?

Solarsun. An old solar sun still company on Long Island. They sold chemical products for the greenhouse industry. That was fun.

Transitioning into civilian life was easier I think when you go to college after the military, instead of before, or never. When everybody’s going crazy on campus you sort of fit in. I grew my hair. I ended up looking like Charlie Manson, with the beard, the hair, the earring. Managed to blow off all that steam over a four year period. Graduated from the University of Colorado in ’75, and I moved to Paris for 7 years.

Did you speak French?

Not a word. But I married a Frenchwoman. I married into a French family and eventually became bilingual. In fact one teacher at the Alliance Francais asked me, “Did you take French in school in America?” and I said “No”, and she said “Good, I don’t have to undo any mistakes then.”

But transitioning was easier in college and in France because the French had had their own problems in Indochina, and so there was sort of a camaraderie between me and them where we both understood just exactly what it was like in that part of the world. It had been an unpleasant part of the world for both of us. So I was able to talk to a lot of their old combatants of the Indochina war, and compare notes, put things in perspective, and then become a happy civilian.

Being in the military was about being a goof-off in 1967, and being a young adult male with experience in 1971. It gave me a lot of discipline. Which I needed as a rebellious kid. It probably saved my life by joining. Because otherwise I would have been on some campus looking like Charlie Manson, smoking dope, drinking wine and probably getting drafted. So I did it my way, I enlisted. I just calculated. It was forty-eight years ago this month that I enlisted. You tell kids today that you were in Vietnam they look at you like you should have either a blue or grey uniform on.

How does your military experience impact you position at Yale?

Back to the discipline. You’re mission oriented. You know what stick-to-it-tiveness is. You learn how to lead. You can’t just bark orders without understanding the character and mentality of each individual that makes up your group. And then there’s realizing that there is also group think, that the unit thinks as a single entity, and thinks in its separate parts too. And you have to empathize. You have to listen. I learned that from a couple of sergeants. They said “Make them say it twice. If you don’t understand it, make them say it three times. Until you understand what they are trying to tell you. Because they won’t always tell you what’s bothering them at first. You may have to pry and dig a little”. And I find that easy, to listen and empathize. And I listen to ideas. I just had a gentlemen in my office telling me about an idea of his, and I always welcome his ideas because I found out as a sergeant myself, if I made up a plan, if somebody said, why don’t we do it this way, okay maybe that way will work. You don’t say, I have more stripes than you therefore you have to listen to me. No, it means you do things as a group. You help each other out. And if you have to, you stand up and protect the people who work for you.

Could you discuss some of the intangible skills that veterans like yourself bring to an organization:

In the military, you learned how to lead, you learned how to follow. You learned how to work as a cohesive unit. You learned how to listen. You listened to what people had to say. Get their input. They may have a good idea, you never know. And I’ve found that to be the case. If you let somebody talk long enough, they’ll come up with a good idea, eventually. Because they’re more intimate with what they do than I am. I can provide direction and I can provide protection. If somebody gets rude with one of my staff I can intervene. I can learn, I can come up with an idea, but I don’t do what they do, day in and day out. They know more about it than I do. When I took over the mail room I had four staff members. It was 11 years ago. I asked them how long they had been there. Each one of them had been there 25 years. So I said, “Well, collectively, you have a hundred years worth of experience here at Yale. I’m probably not going to be able to tell you to do anything, but I’ll learn a lot from you.” They laughed, they said no one had ever spoken to them like that before. You may think of the military as being strict and disciplined, and it is, but when push comes to shove you have to listen to each other.

What do you think about the Yale Veterans Network?

I asked Lori (Rasile, YVN Co-Chairperson) “Have we got a mission?” and she said “We’re still forming.” I would like to do some good. I don’t know if we can be of any help to the ROTC kids, but maybe. Maybe we can talk to them, tell them about our experiences and so forth. I mean that would be more of a history lesson than talking. But maybe we could talk to the ROTC cadets and midshipmen about what it means after you get out. I’d like to do an outreach toward students who are veterans because I’ve walked in those shoes and it’s not always easy. I can always tell if somebody’s just come out of combat. If they smoke, they’re going to chain-smoke. If they drink they’re probably going to drink a lot. And they’re going to talk very quickly. These are all the tell-tale signs. And if there is somebody who can sit down and have a beer and talk with me or Lori or anybody else, not to ask any questions, but let them just let it out, they’re in front of a person who’s been there.

I asked Lori (Rasile, YVN Co-Chairperson) “Have we got a mission?” and she said “We’re still forming.” I would like to do some good. I don’t know if we can be of any help to the ROTC kids, but maybe. Maybe we can talk to them, tell them about our experiences and so forth. I mean that would be more of a history lesson than talking. But maybe we could talk to the ROTC cadets and midshipmen about what it means after you get out. I’d like to do an outreach toward students who are veterans because I’ve walked in those shoes and it’s not always easy. I can always tell if somebody’s just come out of combat. If they smoke, they’re going to chain-smoke. If they drink they’re probably going to drink a lot. And they’re going to talk very quickly. These are all the tell-tale signs. And if there is somebody who can sit down and have a beer and talk with me or Lori or anybody else, not to ask any questions, but let them just let it out, they’re in front of a person who’s been there.

I think the YVN has to formulate a mission. I think we’re kind of wondering who we are right now. We’re really young. Lori is a capable, a very capable leader. I would follow her down the barrel of a cannon. And she wants to do more events, recruiting. Count me in. I’ll do that. I’ll recruit. I’ve tried to recruit people I know are vets, and they said no. Why, I don’t know. I think they’re just reluctant because of how veterans were treated when they got out. I don’t say anything bad happened to my son and his colleagues. But that’s what it is. But everybody when they get out wants to talk to someone. I don’t care if you painted a mess hall in Fort Riley, Kansas for two years and didn’t deploy one inch anywhere near a war zone, it’s still, you did something way different than 99.2% of the rest of the population. When you go into the military it’s like signing your life away. In case of war, use me, don’t use him or her. So you do realize it’s a risk. And once you get out, you don’t really feel out for a few years. You still feel in. I knew guys who got out of Vietnam, who told me they slept on the floor for a year or two after they got out, they couldn’t sleep in a bed. You want to get out, but you can’t break from the life, from the lifestyle. So the YVN has a lot to learn, from our own membership and from the student veterans and maybe from the ROTC kids too.

What ways could Yale help to improve services for veterans?

Yale has been so distanced from the military for the last 40-some odd years that they haven’t developed the mind-set on how to help veterans yet. I’m glad to see that they’ve welcomed the air force and navy ROTC programs back and the military, but it must have been a shock to some Yale staff and faculty to see uniforms back on campus.

These veterans today I think are warmly received everywhere they go. I think America wanted to forget how horrible they were to Vietnam vets, and gush over these veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, and that overall that’s good. But you gotta go beyond the flag-waving and the hand-shakes at the airport, and you gotta listen because they have stories to tell. And not all of them are strung out on PTSD. Each person reacts differently to war than the person next to them. I watched guys faint just because it got so loud and horrendous that their systems shut down. They couldn’t take it anymore. And there was never anything said, because “there but for the grace of God go me and mine.”

These kids coming home now, they have a story to tell. We had IED’s, but not like they have now. One guy was saying, “Imagine that for over a year, you’re looking at each pile of garbage as you’re driving down the street, you’re wondering if that pile of garbage is going to blow up, what happens when you get home and you’re driving down the street? It doesn’t go away. It sticks in your brain.” After a while, you start getting mortgages and kids and those things start pushing those out and fill it up with other things. I think these kids, they’ll survive, but they could also just be checked in on, and the YVN could do that – “How things going … you doing ok … you got your classes set … your books?” I think maybe we could be some help. Maybe there could be an English class for veterans, to teach them how to write. Start it off as noncredit, get an English professor, to come in once a week and discuss how to write. Each of these kids has a story to tell.

I think that what a veteran does when they become a student they’re not going to be dealing with what their 18 year old room-mate is focusing on. Their roommate might be thinking about taking up polo, and this guy here, he needs to say to someone, “Yeah, I saw them playing polo with a head in Afghanistan.” His roommates not going to get that. This guy here he needs to talk to somebody. The YVN could be there for them.